The Development of Centralized Authority

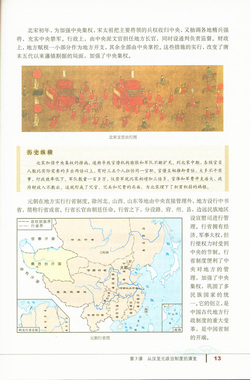

During the Han Dynasty, there existed a long period of time in which the system of prefectures and the feudal system existed alongside each other, the feudal system acting as a support for the royal family, though sometimes rebelling against it as well.

Built on the pacification of the “Seven States Rebellion”, Emperor Wu of Han promulgated the “Edict of Benevolence”, which stipulated that after the death of a local king, that king's eldest son would continue in his place while his brothers would share the divided land and act as feudal lords under the jurisdiction of the throne. This resulted in the contraction and fragmentation of the fiefdoms, and a consequent increase in the power of the central government.

During the Han and Yuan dynasties, conflicts between the local and central authority were sometimes subtle and sometimes obvious, and to a degree influenced the evolution of the political system.

During the Tang Dynasty, the royal court established many Military Commissioners (节度使), who governed military districts (藩镇) for the court, though in reality they enjoyed a great amount of autonomy, economic independence and military power, and would later develop into a separatist power. This separatist movement born in the wake of the An Shi rebellion (安史之乱) continued for more than a hundred years, and seriously damaged the power of the central government.

During the Han Dynasty, there existed a long period of time in which the system of prefectures and the feudal system existed alongside each other, the feudal system acting as a support for the royal family, though sometimes rebelling against it as well.

Built on the pacification of the “Seven States Rebellion”, Emperor Wu of Han promulgated the “Edict of Benevolence”, which stipulated that after the death of a local king, that king's eldest son would continue in his place while his brothers would share the divided land and act as feudal lords under the jurisdiction of the throne. This resulted in the contraction and fragmentation of the fiefdoms, and a consequent increase in the power of the central government.

During the Han and Yuan dynasties, conflicts between the local and central authority were sometimes subtle and sometimes obvious, and to a degree influenced the evolution of the political system.

During the Tang Dynasty, the royal court established many Military Commissioners (节度使), who governed military districts (藩镇) for the court, though in reality they enjoyed a great amount of autonomy, economic independence and military power, and would later develop into a separatist power. This separatist movement born in the wake of the An Shi rebellion (安史之乱) continued for more than a hundred years, and seriously damaged the power of the central government.

During the early years of the Northern Song Dynasy, in order to enrich the central government’s position, Emperor Zu of Song returned the majority of military control back to the central government, and repositioned elite soldiers and influential generals around the country. Administratively, he moved cultured officials from the central government to act as local officials, and created the role of magistrates to act as supervisors. Financially, only a small portion of local taxes were used to pay for local expenses, with the remainder going to the central government coffers. The implementation of these steps transformed the over fifty years of military district (藩镇) separatism that came at the end of the Tang Dynasty, and strengthened central government authority.

The Yuan Dynasty implemented the system of provinces (行省制度) at the local level. Besides the locations directly administered by the central government, such as Hebei, Shanxi, and Shandong, all other locales were designated as the provinces (行中书省), also known as (行省) or just (省). Provincial leaders were appointed directly by the imperial court. Below this province level designation, further divisions included roads (路), provincial seats (苻), prefectures (州), and districts (县) (1), while border areas were managed by pacification offices (宣慰司). These provinces had great economic and military power, but the exercise of their power was often checked by the central government. This provincial system was of great help to the central government’s ability to manage the country, strengthened central authority, and solidified the unification of a multi-ethnic nation. This innovation is one of ancient China’s major advances in government administrative, and is the beginning of China’s province system.

1 - There is a fair amount of ambiguity regarding the proper translations into English for the names of these administrative divisions. I would refer you to both Wikipedia, and Chinese Knowledge, the latter being particularly rigorous.

The Yuan Dynasty implemented the system of provinces (行省制度) at the local level. Besides the locations directly administered by the central government, such as Hebei, Shanxi, and Shandong, all other locales were designated as the provinces (行中书省), also known as (行省) or just (省). Provincial leaders were appointed directly by the imperial court. Below this province level designation, further divisions included roads (路), provincial seats (苻), prefectures (州), and districts (县) (1), while border areas were managed by pacification offices (宣慰司). These provinces had great economic and military power, but the exercise of their power was often checked by the central government. This provincial system was of great help to the central government’s ability to manage the country, strengthened central authority, and solidified the unification of a multi-ethnic nation. This innovation is one of ancient China’s major advances in government administrative, and is the beginning of China’s province system.

1 - There is a fair amount of ambiguity regarding the proper translations into English for the names of these administrative divisions. I would refer you to both Wikipedia, and Chinese Knowledge, the latter being particularly rigorous.

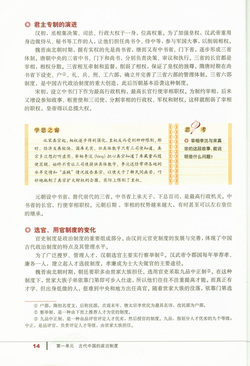

The Slow Rise of Absolute Monarchy

In the early Han Dynasty, the assembly of imperial ministers held policy making, judicial, and administrative power together in one all powerful body. In order to strengthen imperial power, Emperor Wu of Han made his retinues, secretary and other trusted court officials take provincial level positions (尚书令, 侍中) and participate in military affairs in order to counteract the minister’s power.

In the period from the Han to the Sui dynasty, the real power was in the hand of the Department of State Affairs (尚书省), Secretariat (中书令), and the Chancellery (门下省), which gradually formed the “Three Department” system. The Tang Dynasty’s three departments, the Chancellery, the Secretariat and the Department of State Affairs, were respectively responsible for policy, imperial consultation and administration. The officials at the head of these three province system were High Chancellors (宰相), whose power was diffuse. These three departments kept each other in check, and kept the ministers from amassing too much power, thereby ensuring the throne's supremacy. In the Sui and Tang dynasty, the Department of State Affairs was further divided into six departments, Personnel (libu 吏部), Revenue (hubu 戶部), Rites (libu 禮部), War (bingbu 兵部), Justice (xingbu 刑部) and Works (工部), which established and perfected the administrative system of the three province system. This system of three offices and six departments is one of the major innovations of ancient Chinese government administration, which would be used be virtually all dynasty that follow.

At the beginning o the Song dynasty, the Secretariat (中书省), and Chancellery (门下) were designated as the highest administrative organizations, with their highest administrative officials exercising the power of vice chancellor. In order to check the power of these vice chancellors, later the offices of Vice Grand Counselor (参知政事), Military Affairs Commissioner (枢密使), and State Fiscal Commissioner (三司使), each took a share of the chancellors' power, so that all major power returned to the Emperor.

During the Yuan Dynasty the Chancellery replaced the three offices of the previous era. As the kingdom’s most powerful office, above it alone was the Emperor, and below them all the kingdom’s other officials. The leaders of the chancellery exercised power equal to a vice chancellor. Near the end of the Yuan Dynasty, their power increased to ever higher levels, sometimes even able to influence imperial succession.

The Selection of Local Officials

Selecting local officials is an important element in all political systems. The development and improvement of the official selection process of the Han to Yuan dynasties reflects the nature and character of ancient China’s political system and management.

To gather administrative talent from as wide an area as possible, the Han Dynasty implemented the Imperial Selection System. Empeor Wu of Han made his fiefdoms recommend two people every year who were either obedient (孝) or honest (廉), creating a selection process for government officials. This system of Moral Excellence (孝廉) became the primary channel through which officials were chosen for office.

During the Han and Sui dynasties, the royal court wanted to attract more aristocratic youth to take government positions. In order to do this the court adopted the system of Nine Ranks (九品政治 ). Under this system, the sons of aristocratic families could rely on their family status in order to enter official channels, and the importance of being capable gradually became less important. Men born in poor families who had real talent and ability found it hard to reach high positions in the government. As the aristocracy declined, relying on family position in order to choose officials began impossible, and this system of nine ranks could no longer continue.

In the early Han Dynasty, the assembly of imperial ministers held policy making, judicial, and administrative power together in one all powerful body. In order to strengthen imperial power, Emperor Wu of Han made his retinues, secretary and other trusted court officials take provincial level positions (尚书令, 侍中) and participate in military affairs in order to counteract the minister’s power.

In the period from the Han to the Sui dynasty, the real power was in the hand of the Department of State Affairs (尚书省), Secretariat (中书令), and the Chancellery (门下省), which gradually formed the “Three Department” system. The Tang Dynasty’s three departments, the Chancellery, the Secretariat and the Department of State Affairs, were respectively responsible for policy, imperial consultation and administration. The officials at the head of these three province system were High Chancellors (宰相), whose power was diffuse. These three departments kept each other in check, and kept the ministers from amassing too much power, thereby ensuring the throne's supremacy. In the Sui and Tang dynasty, the Department of State Affairs was further divided into six departments, Personnel (libu 吏部), Revenue (hubu 戶部), Rites (libu 禮部), War (bingbu 兵部), Justice (xingbu 刑部) and Works (工部), which established and perfected the administrative system of the three province system. This system of three offices and six departments is one of the major innovations of ancient Chinese government administration, which would be used be virtually all dynasty that follow.

At the beginning o the Song dynasty, the Secretariat (中书省), and Chancellery (门下) were designated as the highest administrative organizations, with their highest administrative officials exercising the power of vice chancellor. In order to check the power of these vice chancellors, later the offices of Vice Grand Counselor (参知政事), Military Affairs Commissioner (枢密使), and State Fiscal Commissioner (三司使), each took a share of the chancellors' power, so that all major power returned to the Emperor.

During the Yuan Dynasty the Chancellery replaced the three offices of the previous era. As the kingdom’s most powerful office, above it alone was the Emperor, and below them all the kingdom’s other officials. The leaders of the chancellery exercised power equal to a vice chancellor. Near the end of the Yuan Dynasty, their power increased to ever higher levels, sometimes even able to influence imperial succession.

The Selection of Local Officials

Selecting local officials is an important element in all political systems. The development and improvement of the official selection process of the Han to Yuan dynasties reflects the nature and character of ancient China’s political system and management.

To gather administrative talent from as wide an area as possible, the Han Dynasty implemented the Imperial Selection System. Empeor Wu of Han made his fiefdoms recommend two people every year who were either obedient (孝) or honest (廉), creating a selection process for government officials. This system of Moral Excellence (孝廉) became the primary channel through which officials were chosen for office.

During the Han and Sui dynasties, the royal court wanted to attract more aristocratic youth to take government positions. In order to do this the court adopted the system of Nine Ranks (九品政治 ). Under this system, the sons of aristocratic families could rely on their family status in order to enter official channels, and the importance of being capable gradually became less important. Men born in poor families who had real talent and ability found it hard to reach high positions in the government. As the aristocracy declined, relying on family position in order to choose officials began impossible, and this system of nine ranks could no longer continue.

During the Sui Dynasty, Emperor Wen of Sui abolished this system of nine ranks, and created a state examination system in order to select government officials. Emperor Yang of Sui began to establish imperial examination branches, and the state examination system was formed. The Tang, Song and Yuan dynasties each inherited this system and further refined it, making it a big evolutionary step for the feudal official selection process. The system tied scholarship, testing, and government duty tightly together, and was instrumental in breaking up monopolies on power, expanding the talent base for officials, and raising the level of sophistication amongst officials. The imperial examination system moved the power of selecting officials from the hands of aristocratic families into the hands of the central government, greatly bolstering the power of the central government. This system, used by successive dynasties, has had a profound and lasting influence.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed